Northern Japan Earthquake

Medical relief activities for ‘The 2011 off the Pacific coast

of Tohoku Earthquake’ by Nippon Medical School (Ver. 2)

Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Nippon Medical School

The 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku Earthquake

On March 11, 2011 at 14:46, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake occurred off the coast of Honshu, Japan. The epicenter was located 130 km offshore of Sanriku. The quake registered a 7 on the Japanese Seismic Intensity scale in Kuribara city in Miyagi prefecture and a 6 over wide areas of Miyagi, Fukushima, Ibaraki, and Tochigi prefectures. The quake was followed by a powerful tsunami that hit the east coast and caused extensive damage to the Tohoku and Kanto regions. The Japanese Meteorological Agency named this earthquake‘The 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku Earthquake’. The exact extent of damage is still being assessed, and as of March 31, 2011, the death toll was up to 10977 with 12994 still missing and 3031 injured (Ministry of Internal affairs: http://www.fdma.go.jp/bn/2011/detail/691.html). In Japan, the mass media are using the term “Higashi-Nihon Daishinsai (East Japan big earthquake) to describe this catastrophic event.

Our medical relief activities for the earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear accident

< Summary >

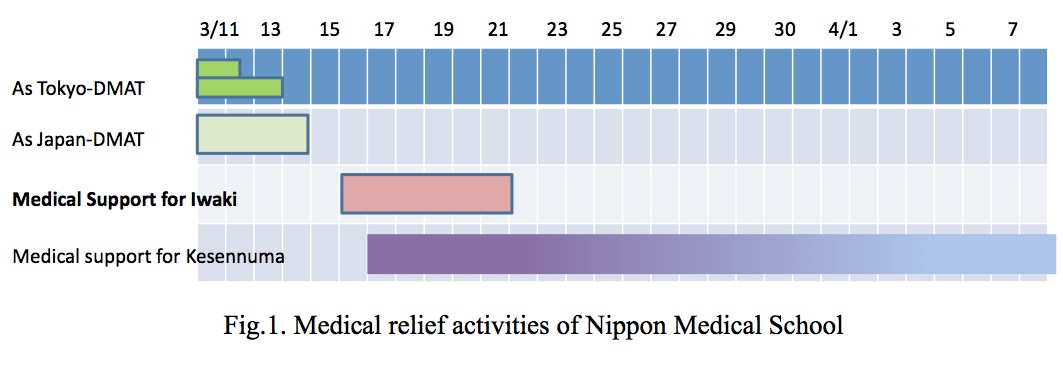

Here we provide an account of our medical relief activities from the onset of the disaster (Fig. 1).

First, our Disaster Medical Assistance Team (DMAT) was deployed as the Tokyo DMAT to Kudan Kaikan, where the ceiling of a hall with an 1112 capacity had partially collapsed as a result of the earthquake. Two hours after the onset, our medical team was deployed to Miyagi as part of the Japan DMAT (J-DMAT), and the rendezvous point was set at Sendai Medical Center. We arrived at 0:12 on March 12 and established a Staging Care Unit (SCU) in the Kasuminome Fort of the Japan Self Defense Force (JSDF) using our multi-purpose medical vehicle (Fig. 2). From this point, a wide-area medical evacuation was performed.

We recruited members of the Nippon Medical School (NMS) team from Tokyo the following day and continued our J-DMAT activities, while another NMS team conducted medical rounds and evaluated medical needs in the affected areas of Shiogama and Tagajyo. We concluded our mission in the superacute phase of the disaster on Mar 14.

From March 17, we began medical rounds at a refuge in Kesennuma, Miyagi, while in the vast Tokyo Metropolis, the Japan Medical Association and the All Japan Hospital Association continued to provide medical relief.

< As a Tokyo-DMAT >

Our Disaster Medical Assistance Team (DMAT) was deployed as the Tokyo -DMAT to Kudan Kaikan, where the ceiling of a hall with an 1112 capacity had partially collapsed as a result of the earthquake. Triage was immediately performed at the scene (Fig. 3), and one severely injured victim was transported to our hospital. At the same time, another team of our DMATs was deployed from NMS Tamanagayama hospital to a shopping center in Machida, Tokyo, where a parkade had collapsed.

< As a Japan-DMAT >

A wide, muddy stream was seen moving rapidly across a residential area near Natori River in Miyagi on live NHK TV. The tsunami also reached Sendai airport, submerging the runway. Every staff, who experienced medical relief activities of Sumatra earthquake Indian Ocean tsunami, assumed this earthquake and tsunami to be same, or worse. Two hours after the onset, our medical team was deployed to Miyagi as part of the Japan DMAT (J-DMAT), using our multi-purpose medical vehicle. The rendezvous point of J-DMAT was set at Sendai Medical Center, where local J-DMAT headquarter in Miyagi was established. We arrived at 0:12 on March 12, which was the fastest of all DMATs of metropolitan area. However, we could not start medical relief activities because no information reached local headquarter due to completely damaged infrastructure of information. Early next morning, 20 of J-DMAT had a meeting together and decided to establish a Staging Care Unit (SCU) in the Kasuminome Fort of the Japan Self Defense Force (JSDF) (Fig. 4), which became the first time to manage SCU in Japan where wide-area medical evacuation was performed. We received patients of hypothermia, burn, multiple trauma, crush syndrome, and etc. from disaster base hospital, on-site to SCU by JSDF helicopter. We managed the patients in SCU, and transported them to hospitals of non-suffered area by ‘Doctor Heli’. The following day, we recruited members of the NMS team from Tokyo and continued our J-DMAT activities, and supported Ishinomaki red-cross hospital, one of disaster base hospital. 80 patients of Red category (immediate), 100 of Yellow category (delayed), and 600 of Green category (minor) were admitted there until the 3rd day of the onset.

In addition to that, many rescued casualties isolated by tsunami were transferred by helicopters of JSDF, Fire department, and etc. Our teams supported Ishinomaki red-cross hospital, and triaged new coming patients until next day, March 14, while another NMS team conducted medical rounds and evaluated medical needs in the affected areas of Shiogama and Tagajyo as a medical team of the All Japan Hospital Association. They left Local Medical Headquarter of Miyagi at 6am, then headed for headquarter of Fire department in Shiogama. There, they received information that Tagajyo city and Shichigahama coast were severely damaged without any medical support.

In medical rounds, we triaged more than 1000 patients (Fig.5), and 4 patients were evacuated because they needed urgent hemodialysis. One patient was transferred to a strong base hospital because of hyperglycemia. In medical rounds of hospitals, clinics, and nursing homes, we did not find severely damaged patients.

We concluded our mission in the superacute phase of the disaster on Mar 14.

< Medical Support for Kesennuma >

From March 17, we began medical rounds at a refuge in Kesennuma, Miyagi, while in the vast Tokyo Metropolis, the Japan Medical Association and the All Japan Hospital Association continued to provide medical relief. This earthquake and tsunami severely damaged Kesennuma, killing 678 people. 1521 are still missing (Ministry of Internal affairs: http://www.fdma.go.jp/bn/2011/detail/691.html). The fire after tsunami burned central of Kesennuma, Uchinowaki and Shishiori area. More than 19,000 residents escaped to refuge. The refuge had no electricity, water supply, gas, or information network on March 17. Moreover, no supply of gasoline had interfered recovery from the catastrophe. Kesennuma city hospital continued to receive patients of emergency, but all outpatient clinics were closed.

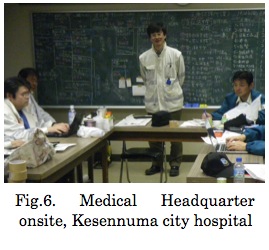

Our medical team had meeting with other medical team, mainly from Tokyo metropolis at Kesennuma city hospital, and analyzed medical needs in Kesennuma city. However, since we could not grasp the needs completely, we decided to divide medical rounds of refugees and our team covered refugees of Karakuwa peninsula from the next day, March 18, where there were around 1500 refugees in sixteen points. Our team was the first team to come in that peninsula after the catastrophe, and took care of fifty patients on average every day in refugee. Patients included wound infection, co-existing diseases like hypertension, diabetes, and cardiac disease. We also searched for basic life needs and health conditions, especially from the view point of prevention of infection. Professor Yokota of NMS was nominated to be the leader of medical relief teams in Kesennuma, and conducted our operation as a whole (Fig.6). Other important mission was postmortem examination, and one of our staffs joined Police teams, on behalf of local doctors.

We grasped the situation of refugee in 104 points until March 20, and established 16 field clinics, covering 1,000 refugees in each clinic. The content of medical relief activities were changed from medical rounds to care at field clinics. This scheme was requested from Japan Medical Association in Kesennuma city.

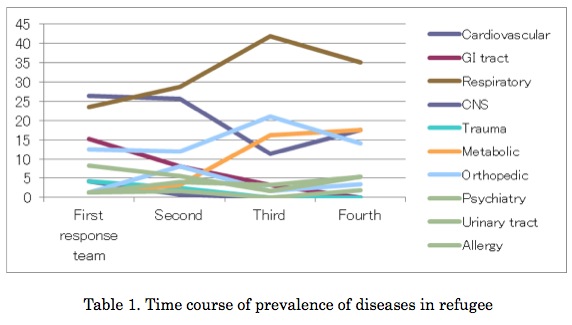

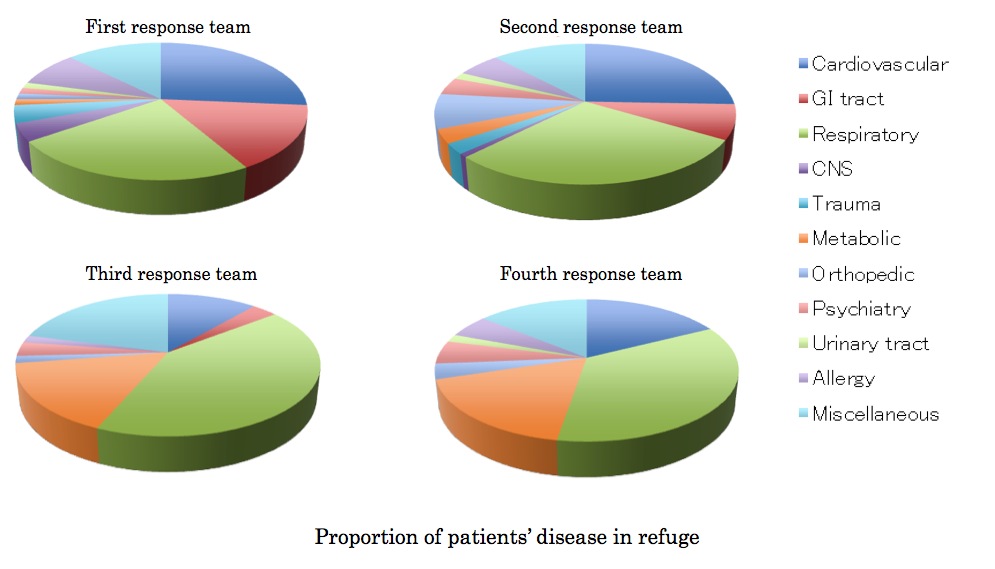

In Karakuwa peninsula, two field clinics were established in Nakai and Karakuwa pubic hall (Fig.7). We continued to provide medical relief activities at the area (Table 1).

< Medical Support for Iwaki >

With regard to the Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant accident, because sufficient medical resources were not readily available in Iwaki city, Fukushima, our NMS team supported the Iwaki Kyoritsu Hospital and evacuated 15 patients to Tokyo from March 17 to March 21.

Acknowledgement

Our gratitude extends to the following at Nippon Medical School: Professor Emeritus Akiro Terashi, Governor, Professor Emeritus Takashi Tajiri, President, Professor Yoshitaka Fukunaga, Director, Hiroshi Koyama, Secretary-general, Shiro Katayama, Manager of the pharmaceutical section at the hospital, and all other colleagues for their invaluable assistance and support during our mission.

Corresponding Author:

Akira Fuse, M.D., Ph.D.

Dept. of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine

Nippon Medical School

1-1-5 Sendagi, Bunkyo-ku Tokyo,

113-8603 Japan

Tel: +81-3-3822-2131 (Ext. 6804)

Fax: +81-3-3821-5102

E-mail: fuse@nms.ac.jp